I always look forward to the winter break. For the holidays and time spent with family and friends, yes, but also for the time for reading. It’s during breaks like these that I travel beyond my typical reading diet, venturing into new genres and stopping to take in those magazine columns I usually skip for the cover stories.

My most recent pleasure was soaking in “In Defense of Facts”, a review by William Deresiewicz of John D’Agata’s writings on the American essay over the years (in this month’s The Atlantic). In summary, Deresiewicz calls into question the way in which pieces of writing are ascribed the genre of “essay”; arguing that this wide application has blurred the lines of what an essay is and isn’t. While Deresiewicz and D’Agata disagree over works that make up the essay genre, both do agree on the essentiality of facts and the role of knowledge.

It is here that I paused to reflect on the complexity and vulnerability of writing. Writing, as an expression of ideas, is a vulnerable act. It is one in which the writer is exposing his/her thought process – showing the reader how s/he wrangles with and makes sense of facts and knowledge to come up an idea. And this brought me right back to the classroom…

When tasked with writing, our students draw upon their fund of knowledge, whether it be from experiences, past readings or a recently read text. The texts to which we expose our students have a direct impact on this fund of knowledge, or prior knowledge. The greater a student’s fund of knowledge, the more facts, knowledge and ideas s/he has to pull from. This is the ticket for more complex and higher order thinking – building on ideas and coming up with new ones altogether. Increasing a student’s fund of knowledge is not only the ticket to better writing but also better reading. In other words, build a student’s prior knowledge and you’ll build their reading level.

Want a student’s reading level to go up? Increase the reading diet to increase prior knowledge.

We often place limits on what students who struggle with reading know by limiting the books they are permitted to read. Yes, “just right books” and “texts at reading level” are important for building reading skills and practice, but if we only expose students to “just right” books we deny them the opportunity to engage in richer ideas and knowledge. We must provide them with access to complex text; students do not have to be reading at the level of the text to draw ideas or understanding from it — we can help them out.

A few quick ways include to provide this help:

- Explicitly teach students to preview a textbook structure and draw meaning from the title, section titles, captions and illustrations

- Front-load vocabulary by previewing key vocabulary words that are essential to understanding the text

- Read passages aloud to the student, stopping to teach the key words in context and to reiterate interesting parts

- Chunk the text and engage in a Reciprocal Teaching routine – this routine makes essential comprehension skills visible and gives students explicit practice with each (https://nysrti.org/intervention-tools/tool:reciprocalteaching/)

To limit our students to only books and texts at their reading level is to limit their world and their experience. We have the tools and the know-how to increase their funds of knowledge and increase their worlds!

Data-Driven Decision-Making

Data-Driven Decision-Making  Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration

Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration  How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?

How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?  Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning

Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning  Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages

Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages  Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?

Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?  Rethinking Classroom Assessment

Rethinking Classroom Assessment  A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices

A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices  Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD

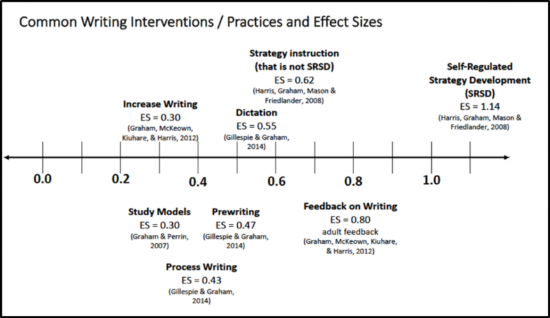

Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD