On Wednesday, March 22nd the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of a student with disabilities in one of the most important special education cases to reach the court in years. The question before the Supreme Court involved the amount of “educational benefit” a student with disabilities received in order to ensure that he/she has been provided “FAPE”, or Free Appropriate Public Education, as required by the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA).

Here are some facts in the case:

(Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, No. 15-827 (March 22, 2017)

- Endrew F. was diagnosed with autism at age two and attended school in Douglas County School District from preschool through fourth grade.

- Endrew’s IEPs largely carried over the same basic goals and objectives from one year to the next, indicating that he was failing to make meaningful progress toward his aims.

- By Endrew’s fourth grade year, his parents had become dissatisfied with his progress. His parents believed that only a thorough overhaul of the school district’s approach to Endrew’s behavioral problems could reverse the trend.

- In April 2010, the school district presented Endrew’s parents with a proposed fifth grade IEP that was, in their view, pretty much the same as his past ones. So, his parents removed Endrew from public school and enrolled him in a private school that specializes in educating children with autism.

- The private school developed a “behavioral intervention plan” that identified Endrew’s most problematic behaviors and set out particular strategies for addressing them. His new school also added heft to Endrew’s academic goals.

- Within months, Endrew’s behavior improved significantly, permitting him to make a degree of academic progress that had eluded him in public school.

- In November 2010, six months after Endrew started at his private school, his parents again met with representatives of the Douglas County School District. The district presented a new IEP. Endrew’s parents considered the IEP no more adequate than the one proposed in April, and rejected it. They were particularly concerned that the stated plan for addressing Endrew’s behavior did not differ meaningfully from the plan in his fourth grade IEP, despite the fact that his new experience suggested that he would benefit from a different approach.

This Court reviewed the standard established in Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176 (1982), that an IEP has to be “reasonably calculated to enable the child to receive educational benefits”. In that decision, the Court simply commented that an educational benefit was evident in the particular case in front of them in which Rowley, who was being educated in a regular classroom, had achieved above average grades. The Court did not provide a test of educational benefit or guidance with respect to students with disabilities who were not integrated into a regular classroom or for whom grade level performance might not be a reasonable goal. In the absence of a test many lower courts have interpreted Rowley as requiring only some or minimal educational benefit for students with disabilities. This is what happened in Endrew F. where the lower court ruled that the school district had met the educational benefit standard by providing “merely more than the de minimus” benefit.

In their March 22 decision, the Court overturned that lower court ruling. Writing for all the justices, Chief Justice John Roberts argued:

“It cannot be right that IDEA generally contemplates grade-level advancement for children with disabilities who are fully integrated in the regular classroom…but is satisfied with barely more than de minimis progress for children who are not. When all is said and done, a student offered an educational program providing “merely more than de minimis” progress from year to year can hardly be said to have been offered an education at all. For children with disabilities, receiving instruction that aims so low would be tantamount to “sitting idly . . . awaiting the time when they were old enough to ‘drop out.’” Rowley, 458 U. S., at 179 (some internal quotation marks omitted). The IDEA demands more.”

The Supreme Court reinforced the concept that the adequacy of an IEP “turns on the unique circumstances of the children for whom it is created.” Deference is based on the application of expertise and judgement of school officials and families/guardians in a collaborative process that results in discernable student progress.

The key messages remain:

- The fundamental function of an IEP is to set out a plan for pursuing academic and functional advancement.

- An IEP must aim to enable the child to make progress towards the general education curriculum regardless of their placement.

- The degree of progress contemplated by the IEP must be appropriately ambitious in light of the child’s unique needs.

- When something isn’t working, we don’t continue to do more of the same.

To learn more about this topic along within the greater concept of educational benefit, join us for our IEP Institutes, which can be found on our training calendar.

Data-Driven Decision-Making

Data-Driven Decision-Making  Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration

Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration  How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?

How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?  Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning

Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning  Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages

Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages  Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?

Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?  Rethinking Classroom Assessment

Rethinking Classroom Assessment  A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices

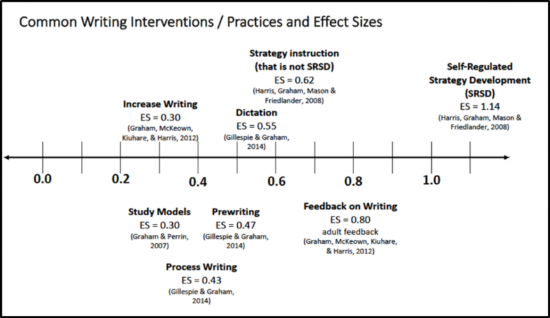

A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices  Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD

Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD