Food for Thought…

A while ago I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Cecile Gleason, an early childhood consultant that the New York State Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports Technical Assistance Center (NYS-PBIS-TAC – say that three times fast!) had invited to work with the NYS preschool behavior specialists. Dr. Gleason shared a lot of valuable information with us around the Pyramid Model and her experiences with implementation. I appreciated that Dr. Gleason not only gave us information about the evidence-based practices encompassed within the Pyramid Model, but was also willing to share personal anecdotes and opinions (always making clear, of course, the distinction between her opinions and research-based facts).

A while ago I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Cecile Gleason, an early childhood consultant that the New York State Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports Technical Assistance Center (NYS-PBIS-TAC – say that three times fast!) had invited to work with the NYS preschool behavior specialists. Dr. Gleason shared a lot of valuable information with us around the Pyramid Model and her experiences with implementation. I appreciated that Dr. Gleason not only gave us information about the evidence-based practices encompassed within the Pyramid Model, but was also willing to share personal anecdotes and opinions (always making clear, of course, the distinction between her opinions and research-based facts).

One thing she mentioned that stuck with me, and that I have been mulling over ever since, was the idea of minimizing the number of transitions students are asked to complete throughout the day. Her feeling was that these transitions are exhausting for young learners, who are repeatedly told they have to stop doing things throughout the day based on someone else’s time table and that we should try to keep them as infrequent as possible. The example she gave was when classrooms have a formalized structure for transitioning students during play center activities. For example, a group of 4-5 students will be assigned to the block area, a second group will be assigned to the play-doh table, and a third group might be assigned to the dramatic play area. A timer is set, and when it goes off, then all of the groups rotate, until each group has had a turn at each center. If you work in the early childhood world, this probably sounds very familiar, as it is quite a common practice. Dr. Gleason, however, recommended that schools avoid structuring the activity this way because it involves a lot of unnecessary transitions for students. Instead, she felt, it was best to let the students select the activities they would like to play with on their own and decide on their own when they were ready to move on to a different activity.

This was the first time I’d ever heard this sort of recommendation against what is typically viewed as a well-structured and organized routine. But I couldn’t help but see her point. Why do we need to add these extra transitions into their day? If a student is working hard on creating a block structure, why should they not have the opportunity to finish the structure in order to go start something new in the play-doh area? Both provide valuable opportunities to work with manipulatives and use the imagination; the student is not missing out on learning by remaining with the materials with which he/she is actively engaged and perhaps he/she may even learn more if they remain there, because they are truly motivated! In fact, persistence with a task is an important skill. Why not let them attend to something they are working on through completion and move on when they are ready? Isn’t the ability to make these kinds of decisions a valuable self-regulation skill? There will not always be an adult nearby telling students when an activity is complete – sometimes students will need to make that determination themselves. For example, deciding when a project or assignment is completed and ready for submission. I can’t help but think that this is an important, lifelong skill, that perhaps we aren’t giving our younger learners enough opportunities to develop.

Back in another life when I was a preschool teacher, in my classroom we used a centers board, which had pictures of each center that was “open” that day. There were a designated number of Velcro spots under each picture, indicating the maximum number of students permitted in that area. Students could choose which center they wanted to play in by placing a picture of themselves onto one of the Velcro spots under the center of their choice. They were free to move to whichever centers they would like throughout the centers period by moving their picture to that area, as long as there was an open space, so that we could avoid having too many students in one area (and thus a safety hazard). This also provided some boundaries and parameters while still allowing the students to exercise choice. I can’t say my rationale for structuring it this way was as well thought-out as Dr. Gleason’s, but this format seemed to work well, and perhaps it’s something that others might find useful in their classrooms if they’re looking to cut back on the number of transitions during the day.

Certainly there is value in having the more structured routines – they help to ensure students sample different items and everyone gets a turn with every activity and by their very nature are more organized and less chaotic. But I think there is a lot to be said for Dr. Gleason’s point too. And if there are a couple of students who choose the same activities every single day, there are other ways to work on that (e.g., don’t have that center available every day; have an individualized activity schedule for that student), that still allow the rest of the students to enjoy their play time and practice making their own decisions.

Anyhow, there’s no one right answer, it’s just something to think about… food for thought!

Data-Driven Decision-Making

Data-Driven Decision-Making  Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration

Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration  How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?

How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?  Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning

Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning  Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages

Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages  Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?

Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?  Rethinking Classroom Assessment

Rethinking Classroom Assessment  A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices

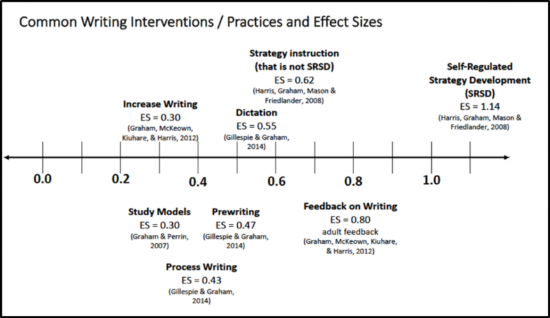

A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices  Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD

Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD