Suddenly, everyone seems to be talking about mindfulness. I hear it talked about in my fitness classes, in classrooms, in professional meetings and in the line at the supermarket! It seemed like a good time to explore the practice, and learn a little more about its research base and application in schools.

What is mindfulness? According to Hooker & Fodor (2008), mindfulness is a very cognizant, purposeful way to be entirely aware of what is happening within us as well as around us, without judgement. Another way of defining it, is “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally, to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p. 145). Mindfulness is learned and practiced through meditation and breathing exercises, during which mental awareness and experiencing the present moment are stressed.

The practice of mindfulness has seen an increase in use by mental health professionals because there is extensive research that suggests it can be quite beneficial in improving mental focus, easing anxiety and depression, and supporting emotional regulation and stress (Hooker & Fodor, 2008). It has also been found to be effective in addressing chronic pain and disease, anxiety, depression, emotional stress, eating disturbances and sleeplessness. For example, the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care and Society at UMass Medical School1 has had over 6,000 doctors refer over 22,000 patients for mindfulness training. The Center reports that these patients experience a 38% reduction in medical symptoms, a 43% reduction in psychological and emotional distress, and a 26% reduction in perceived stress.

Research on how mindfulness affects children in a school environment is challenging because of the diversity in implementation of the practice, the broad range of outcome measurements used and the varying quality of the studies (Zenner, Herrnleben-Kurz & Walach, 2014; Kuyken et al, (2013). Because of this it can be called a promising practice in education, but not an evidence-based practice.

There are a number of suggestive studies however. Mindful Schools, an organization that provides mindfulness training for adults, conducted a study in the 2011-2012 school year with the University of California, Davis. The study involved 937 children and 47 teachers in three Oakland public elementary schools. Students who were instructed in a mindfulness curriculum showed statistically significant greater improvements in their ability to pay attention and participate in class than did controls.

At the Robert W. Coleman Elementary School in Baltimore, staff decided to refer students with behavioral challenges to the “Mindful Moment” room to reflect on what happened and spend 15 minutes doing mindfulness exercises rather than punishing them with detention or suspension. This practice resulted in zero suspensions for the 2016-2017 school year. Researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Penn State University (Knox, 2013) are in the process of studying the effect the program has on children’s moods, relationships with peers and teachers and emotional self-regulation.

After examining these types of studies more carefully, schools might decide to pilot and evaluate mindfulness practices in their school. Hooker & Fodor (2008) caution that mindfulness and meditation should be initially discussed with students as they may have questions and/or misunderstandings. Once any misconceptions are cleared up it is important to structure the environment so that the children will be successful. They recommend short initial meditations until the students become familiar with the activities and building in mindfulness practice every day or as often as possible. While some schools set a few minutes in the morning and at the end of the day when everyone practices mindfulness, Hooker & Fodor suggest that students be taught to be mindful throughout the school day, for instance, when they walk, eat, move, transition, and interact with adults and other students. The goal is for children to learn to use these mindfulness strategies when they need to, at any time during the day. Additionally, they suggest that facilitated group discussions on mindfulness where children share their experiences enhance the practice and help focus their awareness across situations.

So can mindfulness really help students? Mindfulness meditation has been shown to help ease anxiety, depression, and pain in adults. From my reading thus far, the act of teaching students to breathe deeply and to focus their attention seems to have the potential of helping students improve attention and emotional regulation and calm themselves in challenging situations. Because there is not yet an extensive amount of research on the impact of teaching mindfulness to children in schools, a teacher implementing this promising practice should assess the impact on students in his or her classroom by carefully and intentionally collecting data on student behavior and learning.

1Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society. UMass Medical School, http://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/

References

Hooker, E., & Fodor, I. (2008), Teaching Mindfulness to Children. Gestalt Review 12(1): 75-91.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2): 144-156.

Knox, C. (April 3, 2013). Raising Baltimore. Mindful Magazine, www.mindfulschools.org

Kuyken, W, Weare, K, Ukoumunne, O.C., Vicary, R, Motton, N, Burnett, R, Cullen, C. Hennelly, S & Huppert, F. (2013). Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 126-131.

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S & Walach, H (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol, 5: 603.

Data-Driven Decision-Making

Data-Driven Decision-Making  Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration

Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration  How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?

How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?  Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning

Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning  Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages

Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages  Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?

Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?  Rethinking Classroom Assessment

Rethinking Classroom Assessment  A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices

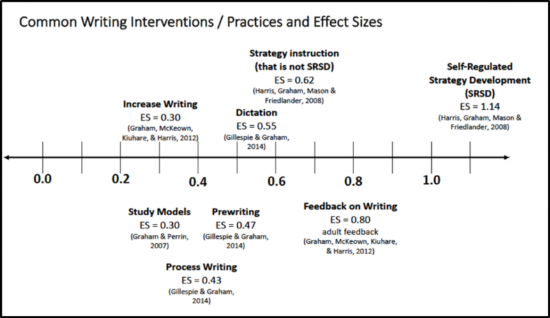

A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices  Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD

Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD