As we embark on a new school year, filled with optimism and hope, we should direct some of our attention to a practice used in Japan, a country with consistently strong academic performance, and how this practice can be adapted to meet the needs of our students, including those with disabilities or from traditionally underperforming backgrounds.

Japan’s academic results are worthy of admiration. Its students are ranked third in the world in both reading and science, and eighth in the world in math according to the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores (Weisenthal, 2013). And this is no anomaly – since these types of international assessments have been given, Japan’s students have consistently fallen within the top ten of developed countries. Additionally, 95 percent of their students graduate high school (OECD, 2011). What is the secret behind the success of the Japanese education system? Many researchers and reporters who follow education point to the Japanese practice of jugyokenkyu, which translates literally as “lesson study.” This unique approach to lesson design holds promise for educators here in the United States as well.

Jugyokenkyu is a collaborative approach to lesson design and revision that follows a series of steps. First, a team of teachers will identify a long-term investigative theme. After gathering research on the theme and content, and studying the curriculum in depth, the team designs a detailed lesson for one selected topic within the theme or unit. Next, one team member delivers the lesson to a group of students while the other team members observe and collect data on student learning. Once the lesson is completed and the students leave, a long and exhaustive discussion of the lesson takes place among the team members. The conversation is focused on the evidence of student learning and proposed lesson revisions. The team redesigns the lesson and another team member re-teaches the lesson to a new group of students. The process culminates with an even larger observation of the redesigned lesson that includes additional faculty and guests, all of whom collect data on student learning. Finally, a formal debriefing and analysis occurs, and the teachers consider questions for subsequent lesson study cycles. This cycle can sometimes continue for three to six years, as Japanese educators have learned to embrace the “slow, steady process of instructional improvement” (Ermeling & Graff-Ermeling, 2014).

The big ideas behind lesson study are teacher collaboration, a focus on student learning, and thoughtful lesson revision based on reflection and constructive feedback. Lesson study requires grit, or perseverance and passion for long time goals, and a growth mindset, or the belief that with practice and reflection we and our students CAN improve. These ideas are a far cry from traditional approaches to lesson design and delivery in the United States where teachers often plan lessons independently in their own classrooms, with little time scheduled for collaboration and sharing; where the focus of observations are on teacher versus student behaviors; and where reflection is centered on whether the lesson went as planned and whether students were engaged, but not on how much they actually learned during the lesson. The Japanese model turns attention to evidence of student learning produced during class – student responses, discussions, class notes, etc. – rather than tests and grades, and challenges teachers to reflect on how they could improve their practice and their lesson to increase student learning.

For teachers of students with disabilities, and in reality virtually ALL teachers are teachers of students with disabilities in our increasingly inclusive school settings, lesson study may prove to be an invaluable tool for improving learning outcomes. When general education or content teachers come together with special education teachers to conduct a lesson study, they all benefit from the cumulative and yet varied experiences of all the teachers. Together they will be able to dissect a lesson and determine whether the planned activities lead to the learning goal. They can anticipate student responses and answers and plan how to address any confusion or misconceptions that will arise. The general education teachers can share their in-depth knowledge of the content or skills to be taught and the special education teachers can share their expertise in strategies and materials to use to meet the needs of diverse students in their class. While every lesson may not lead to the intended outcome, each lesson will then be an opportunity for teachers to hone their craft through honest reflection and on-going lesson improvement based on collaborative observation.

Lesson study is most successful when done on a district- or school-wide basis; however, any teacher can benefit from adopting some of the basic tenets of Jugyokenkyu:

- Collaborate with your colleagues when planning a unit of study – share the responsibility and share the commitment.

- Invite your fellow teachers and administrators to share an open door policy with you whereby they observe your students and you observe theirs, looking for specific evidence of the students’ learning or misunderstandings and sharing that information in a constructive way so that together you can improve your practice and meet your unit goals.

Finally, think of every lesson you teach as an opportunity to learn more about your students and their learning needs, and as a step along the path to highly effective teaching practices.

References

Weisenthal, J. (December 2013). Here’s the New Rankings of Top Countries in Reading, Science, and Math, Business Insider.

OECD (2011), Japan: A Story of Sustained Excellence, in OECD, Lessons from PISA for the United States, OECD Publishing.

Digital Object Identifier

Ermeling, B.A. & Graff-Ermeling, G. (2014). Learning to learn from teaching: a first-hand account of lesson study in Japan, International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, Vol. 3(2), pgs. 170-191.

Data-Driven Decision-Making

Data-Driven Decision-Making  Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration

Increasing Post-School Success through Interagency Collaboration  How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?

How Can We Improve Deeper Learning for Students with Disabilities?  Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning

Positive Classroom Management: Creating an Environment for Learning  Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages

Self-Determination Skills Empower Students of All Ages  Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?

Fidelity of Implementation: What is it and Why does it Matter?  Rethinking Classroom Assessment

Rethinking Classroom Assessment  A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices

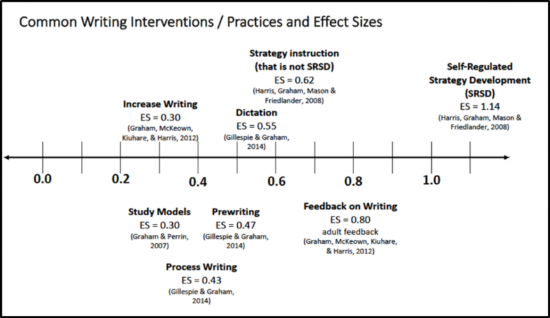

A Three-Step Approach to Identifying Developmentally Appropriate Practices  Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD

Transforming Evidence-Based Practices into Usable Innovations: A Case Study with SRSD